Activity in 2023

The view through the windscreen of my vehicle is quite alarming – there are six armed men in the back of a pick up truck in front of me, all armed with automatic weapons.

Fortunately, they are here to protect me. I am returning after a week of operating in Yemen, which is currently enduring a savage and long running civil war. The injuries that I have seen are all related to weapons of war – bullet injuries and bomb blast injuries.

From the moment that we arrived, we could see men and women in the streets with crutches, negotiating their way through an obstacle course that is their daily life on the dusty streets.

Yemen is an enigma. There is a war going on and there is a front line between warring groups, but civilians do cross the front line frequently – sometimes as part of a commute to work.

Yemen has oil fields – we passed them in the armoured car, and this is the focus for the current battles near Marib. Yet as well as wealth, Yemen has much extreme poverty. There are refugee camps where malnutrition is rife, and feeding programmes are required to keep children nourished. We saw some of the children in the hospital, small for their ages and looking thin and forlorn.

Yemen has varied and spectacular terrain. There are canyons and plains and mountains and deserts, sometimes looking like a lunar landscape and sometimes vast, flat and intimdating. There is also a rich and ancient history – the Queen of Sheba lived in Marib and her palace and temple ruins are still there, as well as Shibam Hadramawt – the ‘Manhattan’ of the desert comprising a vast city of 500 year old high rise buildings that are still inhabited today.

Yet despite all these dichotomies, there is a war in Yemen. This was our focus – to treat people injured in a terrible war. Most patients that have survived to get to hospital have limb injuries. Many head, chest and abdominal injuries are fatal immediately, or within a few hours. Those with limb injuries survive, but suffer contaminated wounds, missing flesh and bone, and a lack of resources and skills to manage the initial injuries well enough to mitigate the disability optimally.

In the conflict zones I have worked in, it is frequently the case that patients treated with plates and nails have had subsequent infection, which can often make the problems faced by the patient worse. These may be the only means of treatment available for local doctors, and they are doing their best. This is why we are here. To help the local doctors offer their patients modern orthopaedic limb reconstruction surgery and provide training.

Luckily, we came prepared with our own orthopaedic hardware to allow us to treat patients with external fixation – which has much lower risks of contaminating or perpetuating infection in wounds. It is paradoxically more uncomfortable for the patients, with metalwork around their limbs instead of hidden inside, but ultimately safer. I was warned that patients would not tolerate external fixation. However most accepted the treatment offered, many having had several operations previously and hoping for a better outcome.

The journey here was convoluted with little sleep over a 32 hour period. The final leg, after three flights, was an overnight 6 hours marathon drive from the airport to Marib. We must have passed through two hundred Yemeni Army check points each way. The variably dressed sentries with their head lights stop each car and check documents. For the most part, they wear sand coloured fatigues and desert boots, but some also wear coats over the top, and some wear the Arabic keffiyeh, wrapped around their heads and necks.

Eventually, we arrived at the city of Marib, home to 3 million, and possibly another 3 million internally displaced persons – what we call refugees in their own country. It is much bigger than I had imagined and strangely adorned with neon lit hotels and other buildings. What a bizarre sight. This is a city that is supposed to be in the middle of a civil war.

There are random missile attacks on Marib – I am not sure if they are guided or not. The week before our mission, there was an attack on a key infrastructure element – the mobile phone mast. Another missile landed in a refugee camp in the middle of nowhere. These didn’t seem random – very much guided – but other attacks seemed to be ‘dumb’ missiles that just appeared to land in random locations, to terrify the local population. Yet life goes on, and people walk in the streets and street vendors open their shops and shoppers haggle at the market to negotiate a price.

The road was atrocious going to the hotel, but the hotel has just been refurbished and was surprisingly comfortable apart from a lack of running water. We sat down to a very late meal, with the security detail on the next table, and their AK47s nonchalantly piled on a table next to them. It was surreal. There was friendly Arabic conversation, with lots of smiles and laughing. I don’t speak Arabic, but it all sounded convivial.

The food was tasty and filling. I especially appreciated the ready sweetened tea and the fresh grape juice.

Unlike the SUV, the air conditioning in the hotel was working, albeit rather noisily, but the noise didn’t stop me from getting to sleep in preparation for the first real day of the mission.

The next day, the journey to the hospital wasn’t long – about 10 minutes. We entered through an archway flanked by armed guards with AK47s, but then, who hasn’t got an AK47 here? Other cars were lining up to enter the hospital grounds, but we skirted around the queue and were immediately allowed in.

The cars weaved in and out of throngs of people, some of whom were on crutches or in wheelchairs – our prospective patients. As we left the cars, some of them seemed to recognise that we were the visiting team, and some of us had xrays thrust in our faces, and one mother was baring her daughters scarred forearm for one of us to inspect.

We squeezed through the throng and followed our contact into the hospital. We were scheduled to meet the Hospital Director first. We were sat down in a large room – his office – in comfortable chairs and offered drinks – cold water, fruit juice in cans and cups of warm sweet tea.

I got out pen and paper and we started the clinic. The first patient was a middle aged man with his xrays tucked under his arm. He had a shoe raise and a lumbar support belt on. We went through his xrays and his story. To cut a long story short, all the patients had all been injured by bomb blasts or gunshot injuries. He had been treated in Egypt and then in Saudi Arabia. In Saudi, they had made his femoral fracture unite, but his right leg was shorter than the left. He also complained of multiple discharges from the leg. At first we believed that this was the result of a bone infection from the injury, but his discharging areas were in his groin and well away from his injuries and previous treatment. The bone had healed, although it was short 4cm, and it seemed more likely that the discharging areas were the result of groin abscesses from other causes. He was advised by my Arabic speaking colleagues that he didn’t need surgery and that the shoe raise seemed to be doing a satisfactory job of equalising his leg lengths.

Some of the patients had been to Egypt or had been promised a trip to Egypt to see a doctor there. This created a real problem for us. They may have been given information that we would contradict. They may also have had surgery that we didn’t agree with. This can be confusing for patients as they have no idea who is right, if anyone at all is right in their advice.

The next patient had been injured by a bomb blast. He had an abdomen like a chess board as there were so many scars, but he had managed to survive and also have a normally functioning bowel. His right leg was also injured. The bone had healed up, but with significant shortening from overlapping of the bone ends, and he also had a deformity with a knock kneed position of his right leg. We studied the xrays and his limb – he had limited movement but functional enough. Without surgery, his knee would wear out prematurely on the outer side. We formulated a plan to correct the deformity and get it to heal – limited goals considering the environment. My colleagues wanted to use a plate to secure the new position. I am not comfortable with metal plates for war injuries, but there was no sign of infection from the last 2 years and we have limited equipment available to us. The plate has to be purchased as well as the accompanying screws. I didn’t really learn who was going to pay for it all, but I assume that it isn’t the patient, as it wasn’t demanded of him.

The next patient was a gunshot wound to the foot and ankle. His foot had an open wound on the inner side, possibly due to infection as it had been three months since the injury. We had brought treatment options for dealing with infection, so this was not now an issue. However, the joints were damaged as well, and this is something for a later date.

Our next patient had suffered a knee injury from a gunshot wound. He had a gap in his bone that needs filling but his knee had not moved for 7 months due to his emergency external fixator to stabilise the bone. We decided on just dealing with the bone loss, which could also possibly be infected, to leave the filling of the defect until later, when the possibility of infection would have been lowered further by debriding or scratching at the surface of the bone to remove dead and infected tissue, and then filling the space with a form of putty with antibiotics in it to kill any bacteria contaminating the area. This type of treatment isnt available here, so we had a better chance of clearing the infection.

Over the morning, we saw a total of 19 of these complex patients with typical chronic war injuries, which were preventing them from functioning normally. Some of them were open to our suggestions and others became agitated, with several walking out as the treatment options offered were not to their liking.

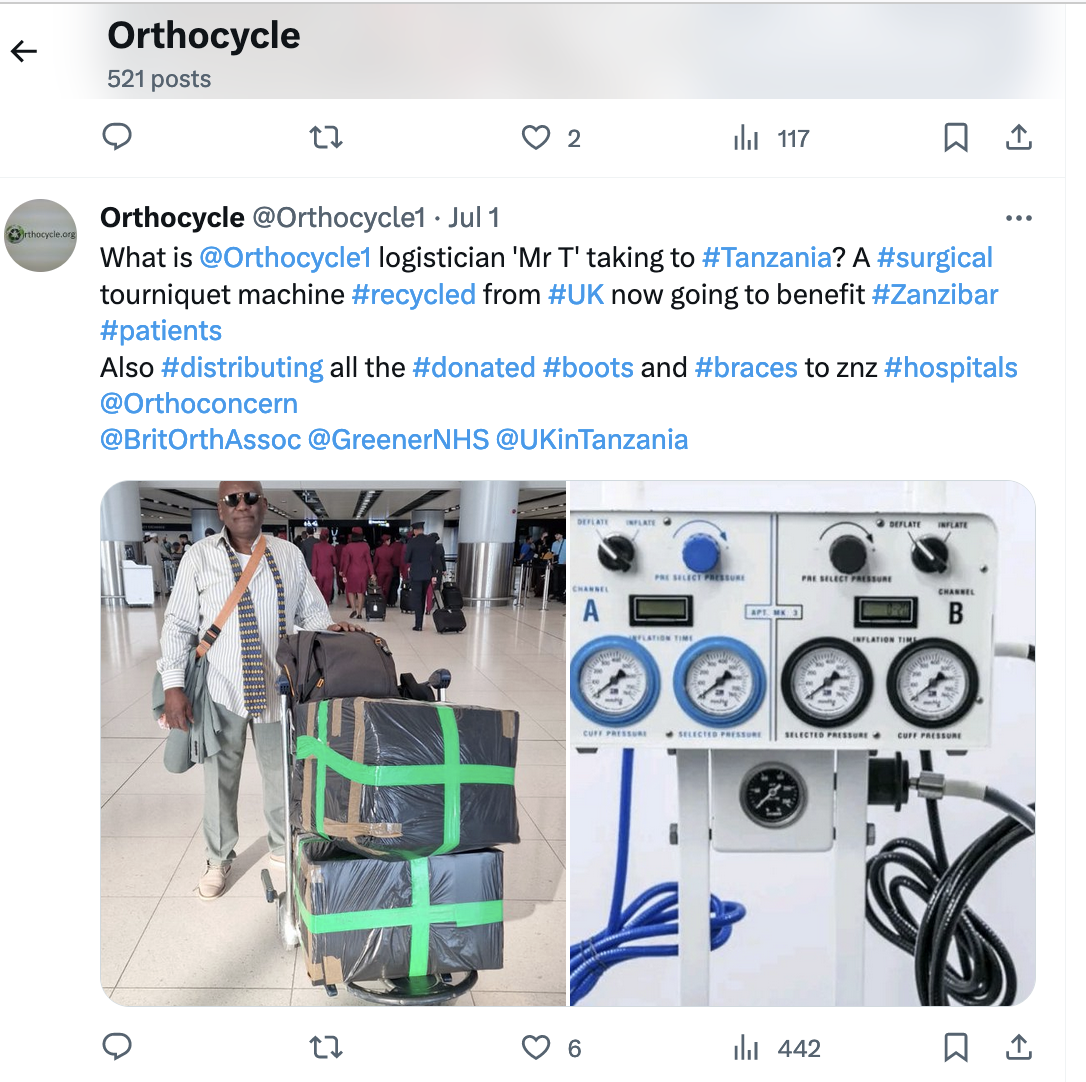

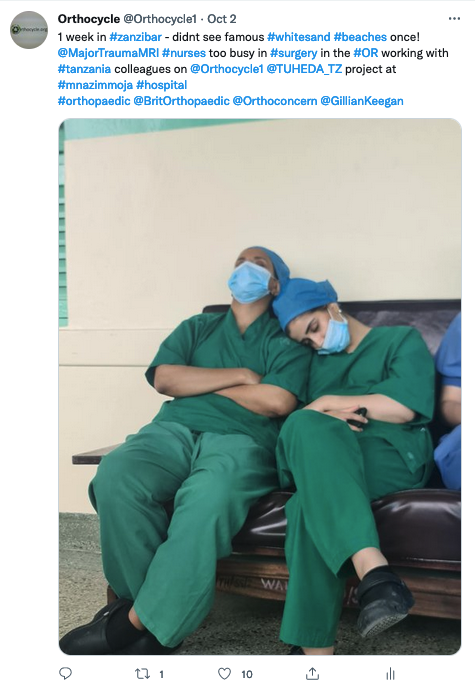

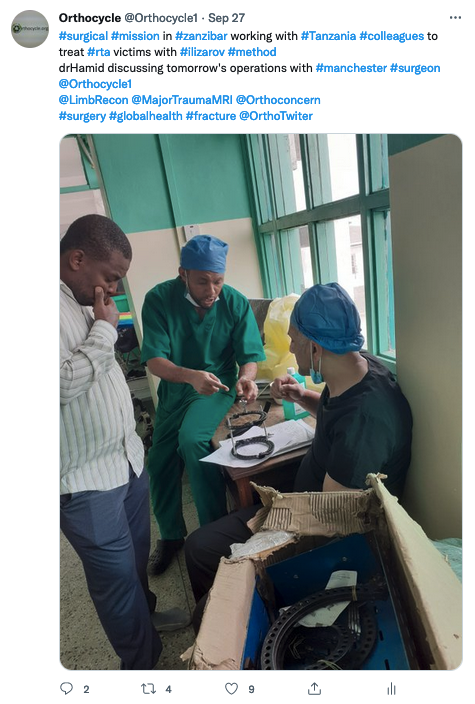

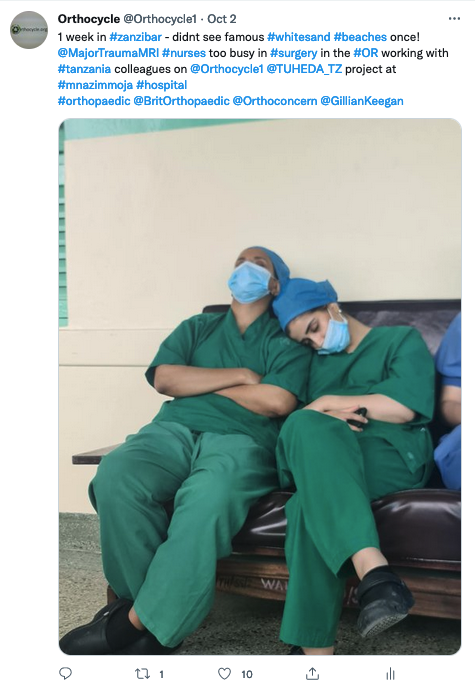

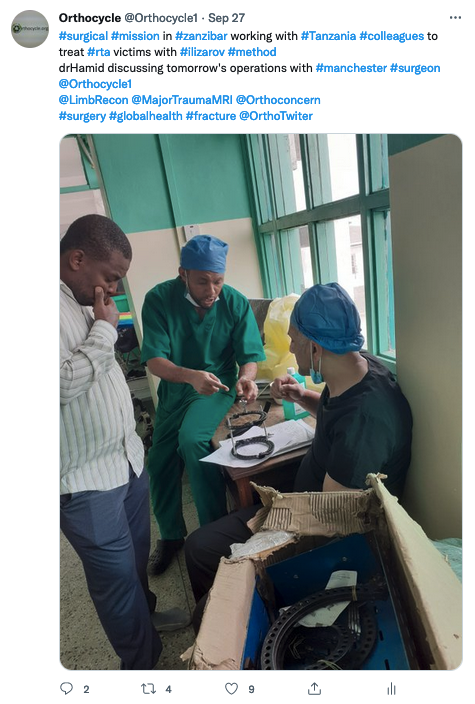

Doing the best with what they have – our colleagues in Tanzania need our recycled surgical hardware and orthotics

I’m currently appreciating a pretty sobering demonstration of the inequities in global health. I am in Tanzania in East Africa, visiting surgical colleagues to evaluate how we can collaborate to improve the treatment of patients here. Although I was here in Tanzania many years ago, the contrast between what facilities that I take for granted in the UK, and those available to orthopaedic surgeons here in Tanzania are striking.

Where can I start? Today we operated on two patients with fractures of their thigh bones. The treatments available are limited by the resources available here. In the UK, we would have a range of surgical implants, a reliable way to sterilise instruments and we would have an xray machine in the operating theatre to provide real time imaging while implants were placed – basic fluoroscopy. Even in war zones, I have had this facility. However, here there are very few implants. For a femoral fracture today, I had to choose an plate from a bag of assorted implants. Of the two metal plates available, one was too big and the other too small. I am pretty sure these plates had been used previously in other patients and then removed. The screws available were mixed types of different diameters and lengths, but a narrow range of sizes. There was no sterilised drill available. Instead, we used a hardware store drill wrapped in surgical towels, which felt worrying. The drill bits were all broken. I couldnt find a single drill that had any tip, never mind a sharp one, for drilling holes for the screws, and in the end we used a K wire, a sharp wire that is not designed for that purpose. We managed to get the job done, and I hope the patient makes a good recovery, but it made a straight forward operation much more complicated and time consuming. The other patient had a metal rod in their femur that had been placed blind – without fluoroscopy – because there is none. The xrays taken after a previous operation showed that the metal rod was not holding the fracture. The operation today used a SIGN nail, which is designed for use without fluoroscopy in developing countries, but the instrumentation had bits missing, and other parts were broken. It is hard enough to operate with a full set of instruments and fluoroscopy, but without these, it means that patient care is compromised. The orthopaedic surgeons here are very good, but without many basic facilities, it is hard for them to offer the care that they want to give their patients. Dr B has completed fellowships abroad, and his orthopaedic knowledge and skills are second to none. However, he knows that he cant give his best treatment in the circumstances of this hospital. He shrugs when I ask him. He is doing his best – he has introduced the WHO checklist amongst other things – but without basic financial resources, he cant do more.

I have seen several patients with tibial fractures who are languishing because they cant afford to pay for emergency treatment. The system here is co-pay – the patient has to pay a part of the cost of their care. However, if they are poor, they dont get an operation, and this can prevent a working person being able to rehabilitate quickly and go back to providing for their family. It is a vicious circle.

There are few orthopaedic surgeons in the whole of Tanzania. There are more in the city of Manchester than this whole country. There is no CT scanner or MRI scanner in this regional hospital. Dr B is trained in arthroscopy and joint replacement but cant do either in this hospital, where there is no equipment and he feels it is not safe.

The NHS is justifiably the envy of the right thinking world. Providing equitable care for all with no prejudice based on ability to pay is something that we dont appreciate enough. I cant say that I will stop moaning about work, but I do value the system that we work in.

Orthocycle has some surgical equipment that has been recycled from the UK, and we are going to send a set of external fixators for Dr B and his colleagues to use. We are also going to come back to help set up a limb reconstruction service. Nursing colleagues from Manchester are also keen to come to help.

However, this hospital needs fluoroscopy, a decent autoclave and more instruments here. This is going to cost a lot for here – but not a great amount in UK terms – £10,000. We need your help to fund this. Please donate at www.orthocycle.org to help us to improve the care patients can get here in Tanzania, as well as other places we work. Even if this is just the cost of a cup of coffee a week, this will allow us to continue this work.

Injured by a bomb at the age of 7 – what kind of world are we living in?

The human impact of war and man made disasters is hard to imagine when our minds are cluttered with the minutiae of our first world problems.

Next time, you are worrying about how you are going to get up the next rung of the career ladder, or book that ‘experience’ that will see you one-up your friends or colleagues, please spare a moment to consider a young man that I met yesterday.

Adnan (not his real name) was only 7 years old living in Syria when a bomb dropped by an aircraft exploded and a fragment of the bomb entered his spine. His spinal cord was damaged and he lost the use of his legs, as well as bladder and bowel control. I wonder if the pilot who dropped the bomb ever thought about who he might have killed or injured.

Adan is now a refugee. He is an orphan. He is reliant on his neighbour (also a refugee) for help, as there are many things that he cant do. However, one thing that he did do was to brighten up our lives. This young man, with his infectious smile, and positive attitude, is quite a remarkable survivor. He touched our hearts, but I fear that the future is going to be difficult for him, as a refugee, with a disability, in a foreign country.

He came into our clinic with an ulcer on his thigh. Adnan has developed a scoliosis, a curvature of the spine, as well as windswept legs, all secondary to his injury. He is using a very basic wheelchair, which doesnt really cater for his lack of sensation, and his bony prominences. In this case the trochanter (the bump at the top of the thigh bone) has caused ulceration of the skin, where it presses on the wheelchair.

Adnan will need bespoke supports for his body within his wheelchair to support his body and prevent ulcerations on insensate skin.

We hope that we can help, and we also hope that you will be able to as well.

In my last posting, I was pleased to announce that we had raised enough money to buy another disabled man an electric wheelchair, so that he could regain some independence. I’m so grateful to those who contributed to the £1500 needed for that wheelchair. The cost of a cup of coffee for you can count to help make a difference for someone who is in desperate circumstances.

You can help to support Adnan by donating to the Orthocycle charity at www.orthocycle.org and using the on screen button. You can use any credit card. Even if it is just the cost of a cup of coffee, it will contribute to our work to help those in need, innocent victims of other people’s wars.

This is the sixteen visit I have made to treat Syrian refugees in three years. Unfortunately, I fear that there is no end to the number of injured, as I see new patients every time, and still more are being injured and killed every day, many of them children like Adnan.

Please share with your contacts, friends and colleagues.

In June, I made an appeal to raise money for one of my Syrian patients who has lost one arm and one leg in the civil war. He couldn’t get around with crutches due to the loss of his hand, and he also couldn’t use a normal wheelchair.

I’m really grateful to those of you who donated towards the wheelchair. I won’t list them all here, but the last £70 came from Clare Cleret from Chartres in France. I will email each of the donors personally to let them know and thank them individually.

As you can see from the photograph, he has now been given an electric wheelchair to give him some more independence. My Syrian colleague, Dr M, delivered the wheelchair, and sent me these photos on Friday. The smile on his face really made my day.

It is moments like this that make running the orthocycle charity worthwhile.

Although this is a good news story, there are so many more people who need help. This might be through orthotics, physiotherapy or mobility scooters. It may be through surgery that we can perform with our Syrian colleagues to heal broken limbs.

There are more and more injured every day. The current attacks on Idlib have killed 500 people since April, including 150 children. There are thousands more who have been injuried.

Please donate to Orthocycle at www.orthocycle.org to allow us to continue with this work.

Amputee Not Asking For Handouts But Desperate

Tonight, driving through the small Turkish town of Reyhanli, a stone’s throw from the Syrian border, I saw this man in the street. I will call him Ahmed, but this isnt his real name. I recognised Ahmed because I operated on him six months ago, as he had a painful nerve ending in his amputated left leg. He was sitting by the side of a road at a set of traffic lights, trying to sell packets of tissue paper to cars that had stopped at the lights.

Ahmed tries to get about with a crutch, but he cant manage well because he has only one arm. He cant use a normal wheelchair, because he cant manage that, again because he has only one arm.

We bought some tissues from him, and we tried to overpay him, but he wouldnt accept the extra money. He has a family, and is trying to make an honest living. It is heart breaking to see him unable to get around independently because of his disability. He was injured in an aerial bombing while at home in Syria, and suffered the traumatic amputation of two limbs.

The town of Reyhanli has a shocking number of amputees. Sitting in a roadside cafe in the town, it is remarkable how many people, especially young amputees, are getting around with crutches, wheelchairs and electric wheelchairs.

I dont normally use my postings to make a direct appeal, but I think that Ahmed’s fate is really shocking, and I believe that he would really benefit from an electric wheelchair to give him some independence back. The price of these locally in Reyhanli is about £1500.

I would be really grateful if you could please make a contribution, if you feel able to, in order to help buy Ahmed an electric wheelchair. Any contribution, no matter how big or small, will help.

You can make a donation at the Orthocycle charity’s website at www.orthocycle.org and as soon as we have raised enough money to buy the wheelchair, I will hopefully post a picture of him in the wheelchair to let you know that this objective has been reached.

Thank you in advance for any contributions. Please re-share with your friends and colleagues, so that we can reach this total.

Donate to Orthocycle by Pressing the Button Below

@Orthocycle1 @SyriaRelief @UOSSM mission last week – 7 ilizarov frames (3 tibial bone transports, 1 hexapod, 2 femora, 1 humerus), 2 tendon transfers, 3 amputation stump revisions…

— Orthocycle (@Orthocycle1) June 19, 2019

Training for 3 syrian surgeons = sustainability for ilizarov treatment. Big thanks to our donors! pic.twitter.com/RmB7eVPpCa

Recycling Works! This boot donated to @Orthocycle1 charity in UK and now worn by syrian refugee after removal of his (also recycled) ilizarov frame!

— Orthocycle (@Orthocycle1) June 19, 2019

Many thanks to Gersh and Lysbeth Lipshen, and all others who have kindly donated orthotics and crutches. @GLipshen @UOSSM pic.twitter.com/1wfbVx9E9w

My Syrian colleague Dr. M telling a patient about how his operation went today.

— Orthocycle (@Orthocycle1) June 11, 2019

His thigh bone has had ten operations – hope our ilizarov frame finally solves the problem. 2 more syrian doctors have come to learn frame surgery techniques with us@Orthocycle1 @SyriaRelief @UOSSM pic.twitter.com/6ATy7GWWwG

Orthocycle Fundraising Dinner 3rd May 2019

Thank you to everyone who came to the fundraising dinner at Sultanahmet Restaurant! I hope that everyone enjoyed their meal and the company. We raised over £500!

Trustee Carol-Ann McArdle explained the concept of Orthocycle. Farhan Ali gave a fascinating talk on his visits to the Gambia to improve orthopaedic services there. Amer Shoaib gave a talk on how the UK benefits from the experience we have abroad, as well as how other countries benefit from the recycling of surgical equipment.

If you would like to donate to Orthocycle, you can click on the Pay Now button or you can make regular contributions by a direct debit.

Fundraising Dinner Friday May 3rd 1930

Sultanahmed Restaurant 1st Floor, Rusholme

Orthocycle will be hosting a fundraising dinner at the Sultanahmet restaurant in Rusholme, Manchester. This event is to bring together friends and supporters to find out more about what work we have done, and what we want to do in the future, with your help.

Please click here to find out more details about the dinner

The Best Laid Plans of Mice and Men….

July 18 2018

Todays picture shows a fairly content Syrian Orthopaedic Surgeon, Dr M, and the surgical team after a hard day’s graft treating Syrian refugees.

Treating Syrian War Casualties – Scarred Physically and Mentally…

July 16, 2018

It’s day one of another joint Orthocycle / Syrian Relief / SBMS / ATAARelief project treating casualties from the ongoing civil war in Syria. I landed at the airport in south east Turkey last night (or early today) at 0200 hours. Today was a full working day organising the logistics and seeing patients in an outpatient clinic, ready for another week of operating.

amer shoaib receiving certificate

examining 9 year old with leg injuries

infected hip joint and sacrum discharging pus

AMER SHOAIB RECEIVES CERTIFICATE OF THANKS

Manchester orthopaedic surgeon Amer Shoaib has just returned from South East Turkey, where he has spent a week working with Syrian surgeons, to treat victims of the civil war in Syria.

At the end of his week’s stay, Amer was presented with a certificate of appreciation by the hospital manager Mahmoud Kouidir.

Eight patients underwent complex external fixation surgery. This surgery is not available within Syria, and the equipment was all recycled or donated.

BIG THANK YOU TO BIOCOMPOSITES!

We are really grateful to our friends at Biocomposites, who have donated some Stimulan for treating infections in our patients. We have used this product, mixed with antibiotics to treat patients who have contaminated bone and soft tissues from war injuries. We have used it to primarily treat injuries of war – the first documented use of antibiotic space fillers for this purpose. We have used the experience from treating Syrian patients back to Manchester, where we used the same product to treat our bomb victims there. Biocomposites supported us with treatment of the Manchester bomb by giving us free Stimulan – we cant thank them enough for their generosity and humanity.

child with congenital deformity

Yasser Jabbar examines a nonplussed infant

Surgeon Yasser Jabbar operates on a child with DDH

MANCHESTER PAEDIATRIC TEAM COMMIT TO ORTHOCYCLE PROJECT

Consultant Paediatric Orthopaedic Surgeons from the Royal Manchester Childrens Hospital have volunteered to visit Turkey to assess and treat children from Syria. These surgeons are specialists in dealing with children’s musculoskeletal problems, from malformed hip joints to malaligned or short limbs.

We have been lucky to have had Dr Yasser Jabbar from Great Ormond Street visit Emel Hospital to perform surgery on children with developmental hip dysplasia and bone loss from injury. This mission was a great success.

The war in Syria affects children in many ways – physically, socially and psychologically. As there is no infrastructure left in the country, children do not have access to normal hospital services. This means that there is no specialised treatment for children with traumatic injuries, and also no treatment for children who have congenital or developmental problems that require input from an orthopaedic surgeon.

The Manchester team will be heading out late in 2017.